سرفصل های مهم

فصل سوم : استراتژی را با موفقیت هماهنگ کنید

توضیح مختصر

- زمان مطالعه 0 دقیقه

- سطح خیلی سخت

دانلود اپلیکیشن «زیبوک»

فایل صوتی

برای دسترسی به این محتوا بایستی اپلیکیشن زبانشناس را نصب کنید.

ترجمهی فصل

متن انگلیسی فصل

CHAPTER 3

Match Strategy to Situation

If Karl Lewin knew anything, it was how to manage in times of crisis. In fact, he’d recently overseen a quick and successful turnaround of European manufacturing operations at Global Foods, a multinational consumer products company. He was less sure, however, that the same sort of approach would be effective in his new role at the firm.

A hard-driving, German-born executive, Karl had acted decisively in Europe to restructure an organization that was broken because of the company’s overemphasis on growth through acquisition and its focus on country-level operations to the exclusion of other opportunities. Within a year, Karl had centralized the most important manufacturing support functions, closed four of the least efficient plants, and shifted a big chunk of production to Eastern Europe. These changes, painful though they were, began to bear fruit by the end of eighteen months, and operational efficiency improved dramatically.

But no good deed goes unpunished. Karl’s success in Europe led to his appointment as the executive vice president of supply chain for the company’s core North American operations, headquartered in New Jersey. The job was much bigger than the earlier one, combining manufacturing with strategic sourcing, outbound logistics, and customer service.

In contrast to the situation in Europe, North American operations were not in immediate crisis—something Karl recognized was the essence of the problem. The organization’s long-term success had only recently shown signs of slipping. The preceding year, industry benchmarks had placed the company’s manufacturing performance slightly below average in overall efficiency, and in the lower one-third in the crucial area of customer satisfaction with on-time delivery. Mediocre scores, to be sure, but nothing that screamed “turnaround.” Meanwhile, Karl’s own assessment indicated that serious problems were brewing. The business was addicted to fighting fires; managers reveled in their ability to react well in crises rather than prevent problems in the first place. Karl believed it was only a matter of time before major failures occurred. Furthermore, executives relied too much on gut feelings to make critical decisions, and information systems provided too little of the right kind of objective data. These shortcomings contributed, in Karl’s view, to widespread, unfounded optimism about the organization’s future.

To take charge successfully, you must have a clear understanding of the situation you are facing and the implications for what you need to do and how you need to do it. From the outset, leaders like Karl need to focus on answering two fundamental questions. The first question is, What kind of change am I being called upon to lead? Only by answering this question will you know how to match your strategy to the situation. The second question is, What kind of change leader am I? Here the answer has implications for how you should adjust your leadership style. Careful diagnosis of the business situation will clarify the challenges, opportunities, and resources available to you.

Using the STARS Model

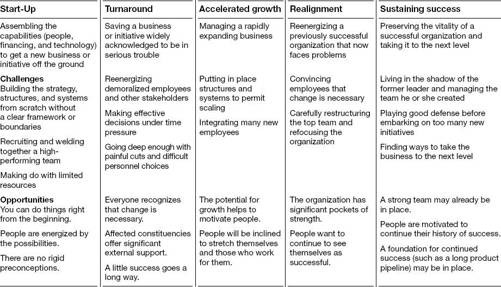

STARS is an acronym for five common business situations leaders may find themselves moving into: start-up, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, and sustaining success. The STARS model outlines the characteristics and challenges of, respectively, launching a venture; getting one back on track; dealing with rapid expansion; reenergizing a once-leading business that’s now facing serious problems; and inheriting an organization that is performing well and then taking it to the next level.

In all five of the STARS situations, the eventual goal is the same: a successful and growing business. However, the challenges and opportunities, summarized in table 3-1, vary in predictable ways depending on which situation you are experiencing.

What are the defining features of the five STARS situations? In a start-up, you are charged with assembling the capabilities (people, funding, and technology) to get a new business, product, project, or relationship off the ground. This means you can shape the organization from the outset by recruiting your team, playing a major role in defining the agenda, and building the architecture of the business. Participants in a start-up are likely to be more excited and hopeful than members of a troubled group facing failure. But at the same time, employees of a start-up are typically much less focused on key issues than those in a turnaround, simply because the vision, strategy, structures, and systems that channel organizational energy are not yet in place.

In a turnaround, you take on a unit or group that is recognized to be in deep trouble and work to get it back on track. A turnaround is the classic burning platform, demanding rapid, decisive action. Most people understand that substantial change is necessary, although they may be in disarray and in significant disagreement about what needs to be done. Turnarounds are ready-fire-aim situations: you need to make the tough calls with less than full knowledge and then adjust as you learn more. In contrast, realignments (and sustaining-success assignments) are more ready-aim-fire situations. Turning around a failing business requires the new leader to cut it down to a defensible core fast and then begin to build it back up. This painful process, if successful, leaves the business in a sustaining-success situation. If efforts to turn around the business fail, the result often is shutdown or divestiture.

In an accelerated-growth situation, the organization has begun to hit its stride, and the hard work of scaling up has begun. This typically means you’re putting in the structures, processes, and systems necessary to rapidly expand the business (or project, product, or relationship). You also likely need to hire and onboard a lot of people while making sure they become part of the culture that has made the organization successful thus far. The risks, of course, lie in expanding too much too fast.

Start-ups, turnarounds, and accelerated-growth situations involve much resource-intensive construction work; there isn’t much existing infrastructure and capacity for you to build on. To a significant degree, you get to start fresh or, in the case of accelerated growth, to build on a strong foundation. In realignments and sustaining-success situations, in contrast, you enter organizations that have significant strengths but also serious constraints on what you can and cannot do. Fortunately, in these two situations you typically have some time before you need to make major calls. This is good, because you must learn a lot about the culture and politics and begin building supportive coalitions.

Because of internal complacency, erosion of key capabilities, or external challenges, successful businesses tend to drift toward trouble. In a realignment, your challenge is to revitalize a unit, product, process, or project that has been drifting into danger. The clouds are gathering on the horizon, but the storm has not yet broken—and many people may not even see the clouds. The biggest challenge often is to create a sense of urgency. There may be a lot of denial; the leader needs to open people’s eyes to the fact that a problem actually exists. This was the situation facing Karl in North America. Here, the good news is that the organization likely has at least islands of significant strength (good products, customer relationships, processes, and people).

In a sustaining-success situation, you are shouldering responsibility for preserving the vitality of a successful organization and taking it to the next level. This emphatically does not mean that the organization can rest on its laurels. Rather, it means you need to understand, at a deep level, what has made the business successful and position it to meet the inevitable challenges so that it will continue to grow and prosper. In fact, the key to sustaining success often lies in continuously starting up, accelerating, and realigning parts of the business.

A key implication is that success in transitioning depends, in no small measure, on your ability to transform the prevailing organizational psychology in predictable ways. In start-ups, the prevailing mood is often one of excited confusion, and your job is to channel that energy into productive directions, in part by deciding what not to do. In turnarounds, you may be dealing with a group of people who are close to despair; it is your job to provide them with a concrete plan for moving forward and confidence that it will improve the situation. In accelerated-growth situations, you need to help people understand that the organization needs to be more disciplined and get them to work within defined processes and systems. In realignments, you will likely have to pierce the veil of denial that is preventing people from confronting the need to reinvent the business. Finally, in sustaining-success situations, you must invent the challenge by finding ways to keep people motivated, combat complacency, and find new direction for growth—both organizational and personal.

You cannot figure out where to take a new organization if you do not understand where it has been and how it got where it is. In Karl’s realignment situation, for example, it is essential that he understand what made the organization successful in the past and why it drifted into trouble. To understand your situation, you must put on your historian’s hat.

But if you’re not leading a large business, can you still use the STARS model to understand the challenges you face? Absolutely. You can apply it regardless of your level in the organization. You may be a new CEO taking over an entire company that is in start-up mode. Or you could be a first-line supervisor managing a new production line, a brand manager launching a new product, an R&D team leader responsible for a new product development project, or an information technology manager responsible for implementing a new enterprise software system. All of these situations share the characteristics of a start-up. Similarly, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, and sustaining success arise at all levels, in companies large and small.

Diagnosing Your STARS Portfolio

In reality, you’re unlikely to encounter a pure and tidy example of a start-up, turnaround, accelerated-growth, realignment, or sustaining-success situation. At a high level your situation may fit reasonably neatly into one of these categories. But as soon as you drill down, you will almost certainly discover that you’re managing a portfolio—of products, projects, processes, plants, or people—that represents a mix of STARS situations. For instance, you may be taking over an organization that enjoys incremental growth with successful products and in which one group is launching a line of products based on a new technology. Or you may be working to turn around a company that has a couple of high-performing, state-of-the-art plants.

The next step in applying the STARS model is to diagnose your STARS portfolio; you must figure out which parts of your new organization belong in each of the five categories. Take time to assign the pieces of your new responsibilities (such as products, processes, projects, plants, and people) to the five categories using table 3-2. Given this arrangement, how will you manage the various pieces differently? This exercise will help you to think systematically about challenges and opportunities in each piece. It will also supply you a common language with which to talk to your new boss, peers, and direct reports about what you are going to do and why.

Leading Change

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to leading change. This is why it’s important to be clear about the STARS mix. Using the STARS model, Karl was able to recognize the clear differences between the realignment situation he was heading into (where problems were gradually mounting, but there was no crisis to drive action) and the dramatic turnaround he had successfully managed in Europe (where urgent needs demanded rapid, radical surgery), and he identified the associated implications for how he needed to lead change and manage himself. If Karl had treated his new situation as a turnaround and tried to conduct radical surgery, he probably would have incurred both active and passive resistance, undermining his ability to realize needed change, especially because he was an outsider and therefore vulnerable to being isolated and undercut. Recognizing what was required in North American operations, Karl adopted a more measured approach.

Armed with insight into your STARS portfolio and the key challenges and opportunities, you will adopt the right strategies for leading change. Doing so means, however, adopting the approaches laid out in this book for creating momentum in your next 90 days. Specifically, you must establish priorities, define strategic intent, identify where you can secure early wins, build the right leadership team, and create supporting alliances. Let’s look at what Karl did differently in the turnaround and realignment situations he faced.

The starting point, of course, was focused learning. In the turnaround situation in Europe, Karl needed to rapidly assess the organization’s technical dimensions—strategy, competitors, products, markets, and technologies—much as a consultant would. In his new leadership role in North America, Karl’s learning challenge was markedly different. Technical comprehension was still important, obviously, but cultural and political learning mattered more. That’s because internal social dynamics often cause successful organizations to drift into trouble, and because getting people to acknowledge the need for change is much more a political challenge than a technical one. Particularly for a newcomer to the organization, as Karl was, a deep understanding of the culture and politics is a prerequisite for leadership success—and even survival.

Likewise, as Karl worked to establish priorities, he had to weigh the demands of the situation. The European turnaround required radical surgery. The strategy and organizational structure of the business were preventing it from achieving its goals and had to be changed quickly. So Karl closed plants, shifted production, and cut the workforce dramatically. He also rapidly centralized important manufacturing functions in order to reduce fragmentation and cut costs. The North American realignment, in contrast, didn’t call for an immediate transformation of strategy or structure. There weren’t any major capacity or productivity problems, so plant closures weren’t necessary. The manufacturing functions were already centralized and strong. The real problems lay in systems, skills, and culture. It therefore made sense for Karl to focus on those areas.

Situational factors also played a large role in how Karl built his leadership teams in the two situations. To expeditiously turn around the European business, Karl cleaned house at the top of the organization and recruited most of the new senior talent from the outside. In North America, however, the leadership team he inherited was already quite strong. Still, he realized he needed to make a few high-payoff changes in the roster. A couple of central manufacturing roles required leaders with stronger technical skills to support the systems changes he planned to make, and there was an influential manager who, despite Karl’s best efforts, didn’t grasp the need for change; in fact, the manager’s inaction threatened to undermine Karl’s leadership. That person’s departure sent a crucial message to the rest of the organization. Meanwhile, Karl promoted from within to fill that role and others, and that helped rally the organization behind his plans. People came to see that he wasn’t only focusing on the weaknesses of the business but was also appreciative of its strengths.

Finally, Karl had the good judgment to secure early wins differently in the two situations. In turnarounds, leaders must move people out of a state of despair. Karl did that in Europe by closing ailing plants and shifting production, actions that refocused the organization on its core strengths and helped cut unnecessary projects and initiatives. In the realignment, in contrast, Karl’s most important early win was to raise people’s awareness of the need for change. He accomplished that by putting more emphasis on facts and figures; he revamped the company’s performance metrics in manufacturing and customer service to focus employees’ attention on critical weaknesses in those areas, and he also introduced external benchmarks and hard-nosed assessments by respected consultants—drawing on impartial voices from outside the company to help make his case. These actions enabled him to pierce the unfounded optimism and send an important message to the rest of the organization.

Key differences between leading change in turnaround and realignment situations are summarized in table 3-3.

Managing Yourself

The STARS state of your organization also has implications for the adjustments you’ll need to make to manage yourself. This is particularly true when it comes to determining leadership styles and figuring out whether you are reflexively a “hero” or a “steward.” In turnarounds, leaders are often dealing with people who are hungry for hope, vision, and direction, and that necessitates a heroic style of leadership—charging against the enemy, sword in hand. People line up behind the hero in times of trouble and follow commands. The premium is on rapid diagnosis of the business situation (markets, technologies, products, strategies) and then aggressive moves to cut back the organization to a defensible core. You need to act quickly and decisively, often on the basis of incomplete information.

Clearly, this was the case for Karl in Europe. He immediately took charge, diagnosed the situation, set direction, and made painful calls. Because the outlook was bleak, people were willing to act on his directives without offering much resistance.

Realignments, in contrast, demand from leaders something more akin to stewardship or servant leadership—a more diplomatic and less ego-driven approach that entails building consensus for the need for change. More subtle influence skills come into play; skilled stewards have deep understandings of the culture and politics of their organizations. Stewards are more patient and systematic than heroes in deciding which people, processes, and other resources to preserve and which to discard. They also painstakingly cultivate awareness of the need for change by promoting shared diagnosis, influencing opinion leaders, and encouraging benchmarking.

In his North America appointment, Karl needed to learn to temper some of his heroic tendencies; he had to make careful assessments, move deliberately toward change, and lay a foundation for sustainable success. Whether any leader in transition can adapt her personal leadership strategy successfully depends greatly on the ability to embrace the following pillars of self-management: enhancing self-awareness, exercising personal discipline, and building complementary teams.

Because of their differing imperatives, it is easy for heroes to stumble in realignment and sustaining-success situations and for stewards to struggle in start-ups and turnarounds. The experienced turnaround person facing a realignment is at risk of moving too fast, needlessly causing resistance. The experienced realignment person in a turnaround situation is at risk of moving too slowly and expending energy on cultivating consensus when it is unnecessary to do so, thus squandering precious time.

This is not to say that people who are natural heroes cannot get in touch with their inner stewards and vice versa. Good leaders can succeed in all five of the STARS situations, although no one is equally good at all of them. It is essential to make a hardheaded assessment of which of your skills and inclinations will serve you well in your particular situation and which are likely to get you into trouble. Don’t arrive ready for war if what you need is to build alliances.

You also need to remember that leadership is a team sport. Your STARS portfolio has implications for the precise mix of heroes and stewards (every organization needs both) on your leadership team. Karl willed himself toward stewardship in North America, but he knew he more naturally and effectively played the hero role. The implications of this bit of self-awareness were threefold. First, he needed to stock his team with some natural stewards to whom he could turn for wise counsel (lest he go off half-cocked) and to whom he could delegate some of the necessary outreach. Second, he had to identify where it actually made sense to focus some of his heroic energies. After all, every organization, even the most successful, has parts that are in serious trouble. As long as he didn’t start setting fires just to fight them and didn’t jeopardize the larger goal of realigning the business, this was an appropriate way to achieve a balance. Third, Karl needed to take into consideration STARS preferences and abilities as he hired, promoted, and assigned people to key projects.

Rewarding Success

The STARS framework has implications for how you should evaluate the people who work for you, and for the culture you want to create. Data from the Harvard Business Review Transition Survey helps illustrate this essential point. Participants were asked which of the STARS situations they thought were most challenging and in which they would most prefer to be. The results, summarized in table 3-4, are illuminating. The most challenging situation was assessed to be realignment, followed by sustaining success and turnaround. Start-up and accelerated growth were assessed as being significantly easier. However, when it came to preferences, the pattern reversed, with start-up being (by far) the most popular, followed by turnaround and accelerated growth.

This is not a surprising finding, and the underlying reasons are revealing. It is not the case that people are drawn to the easy situations. Rather, they are drawn to situations that are (1) more fun and (2) get more recognition.

A successful start-up is a visible and easily measurable individual accomplishment, as is a successful turnaround. In a realignment, in contrast, success consists of avoiding disaster. It is hard to measure results in a realignment when success means that nothing much happens; it’s the dog that doesn’t bark. Also, success in realignment requires painstakingly building awareness of the need for change, and that often means giving credit to the group rather than taking it yourself. As for rewarding sustaining success, people seldom call their local power company to say, “Thanks for keeping the lights on today.” But if the power goes off, the screaming is immediate and loud.

There is a paradox inherent in rewarding people lavishly for successfully turning around failing businesses (or starting exciting new ventures). Few high-potential leaders show much interest in realignments, preferring the action and recognition associated with turnarounds (and start-ups). So who exactly is responsible for preventing businesses from becoming turnarounds? And does the fact that companies reward turnarounds (and do not know how to reward realignments) make it more likely that businesses will end in crisis? Skilled managers can seemingly count on less-accomplished people to mess up businesses so that they can come charging to the rescue.

The more general point, of course, is that performance must be evaluated and rewarded differently in the different STARS situations. The performance of people put in charge of start-ups and turnarounds is easiest to evaluate, because you can focus on measurable outcomes relative to a clear prior baseline.

Evaluating success and failure in realignment and sustaining-success situations is much more problematic. Performance in a realignment may be better than expected, but still poor. Or it may be that nothing much seems to happen, because a crisis was avoided. Sustaining-success situations pose similar problems. Success may consist of a small loss of market share in the face of a concerted attack by competitors or the eking out of a few percentage points of top-line growth in a mature business. The unknown in both realignments and sustaining-success situations is what would have happened if other actions had been taken or other people had been in charge—the “as compared to what?” problem. Measuring success in such situations takes much more work, because to assess the adequacy of their responses, you must have a deep understanding of the challenges new leaders face and the actions they are taking.

Closing the Loop

Your understanding of the mix of STARS situations inevitably will deepen and shift as you learn more about your new organization. Plan to return to this chapter periodically to reassess your diagnosis of your organization, and think about the implications for what needs to be done and who needs to do it.

MATCH STRATEGY TO SITUATION—CHECKLIST

What portfolio of STARS situations have you inherited? Which portions of your responsibilities are in start-up, turnaround, accelerated-growth, realignment, and sustaining-success modes?

What are the implications for the challenges and opportunities you are likely to confront, and for the way you should approach accelerating your transition?

What are the implications for your learning agenda? Do you need to understand only the technical side of the business, or is it critical that you understand culture and politics as well?

What is the prevailing climate in your organization? What psychological transformations do you need to make, and how will you bring them about?

How can you best lead change given the situations you face?

Which of your skills and strengths are likely to be most valuable in your new situation, and which have the potential to get you into trouble?

What are the implications for the team you need to build?

مشارکت کنندگان در این صفحه

تا کنون فردی در بازسازی این صفحه مشارکت نداشته است.

🖊 شما نیز میتوانید برای مشارکت در ترجمهی این صفحه یا اصلاح متن انگلیسی، به این لینک مراجعه بفرمایید.